ARCHAEO-POETRY

Adopting the perspective of an archaeologist, the banality of everyday urban life transforms into significant information about contemporary culture.

.adopting the perspective of an archaeologist the banality of everyday urban life transforms into significant information about contemporary culture.

Fundamental Questions

Can we perceive what is unique, special and beautiful in the cultures of our time? Are we even striving to recognize their essence?

My practice proposes a multidisciplinary, interactive approach that reflects these considerations and provokes a positive discourse with a poetic gaze on reality as it is and reality as it could be.

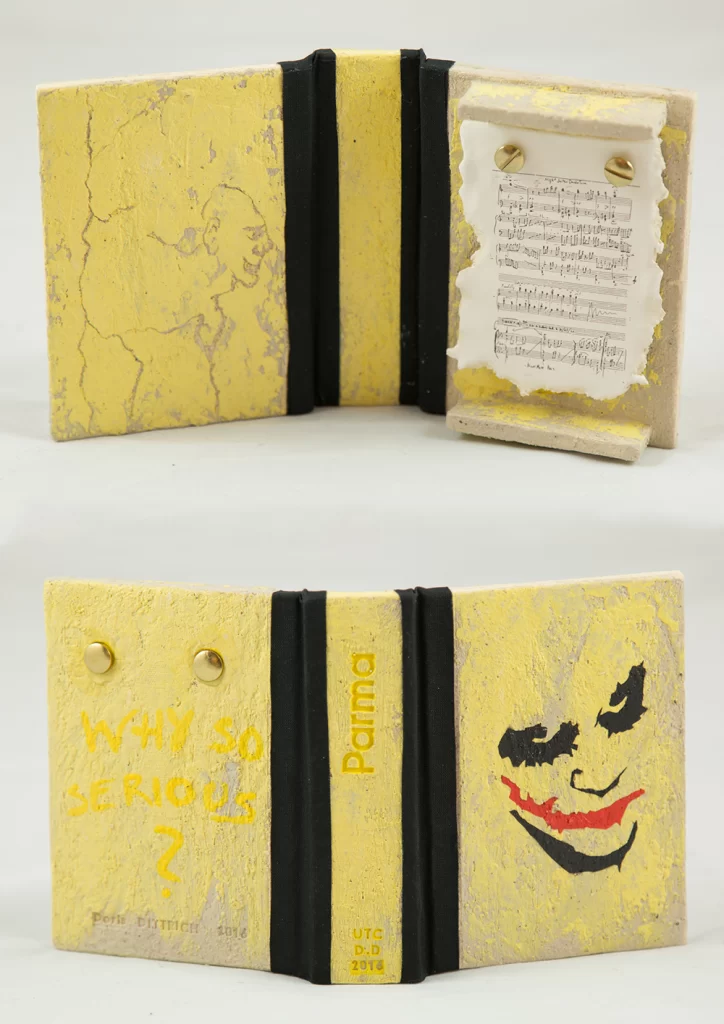

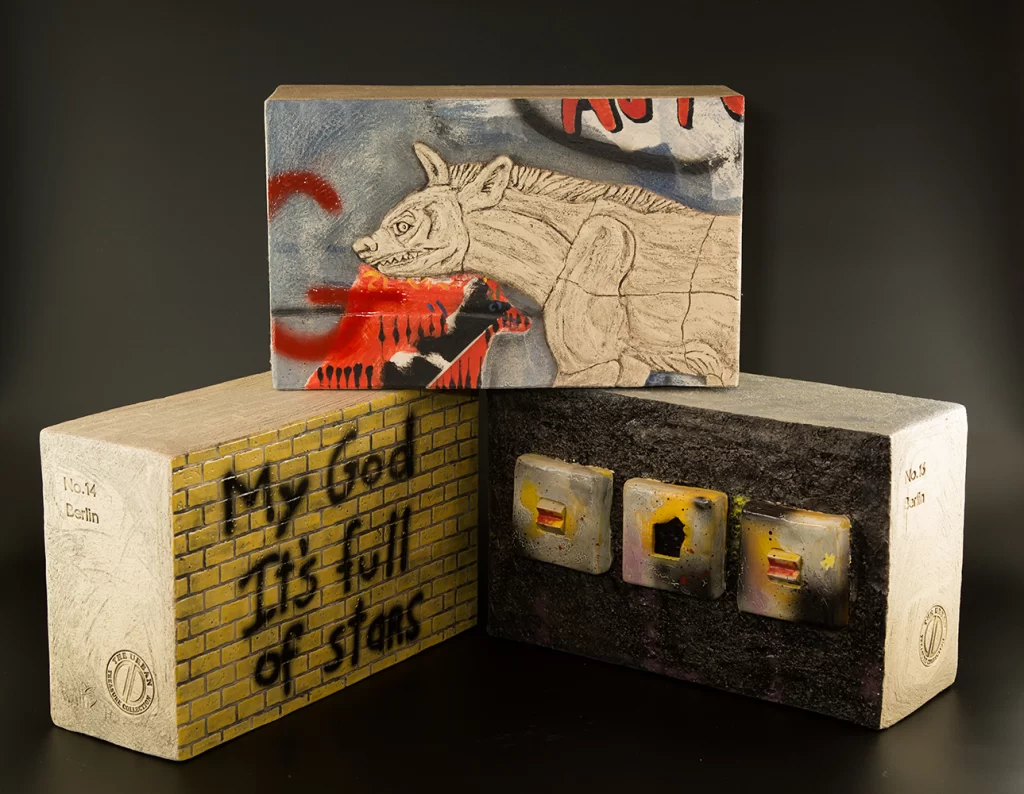

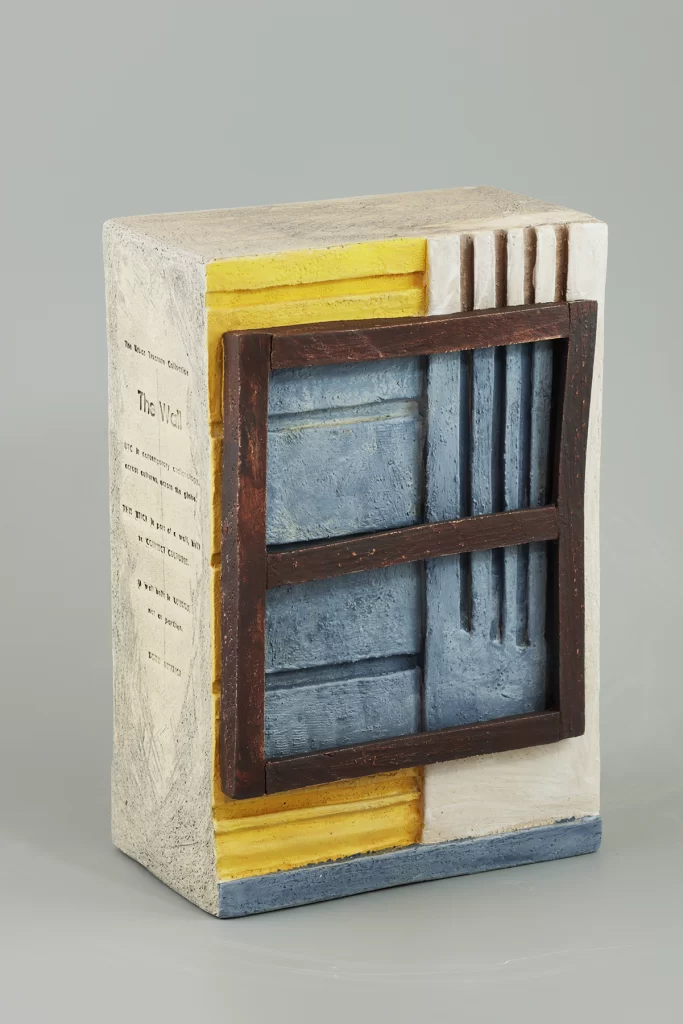

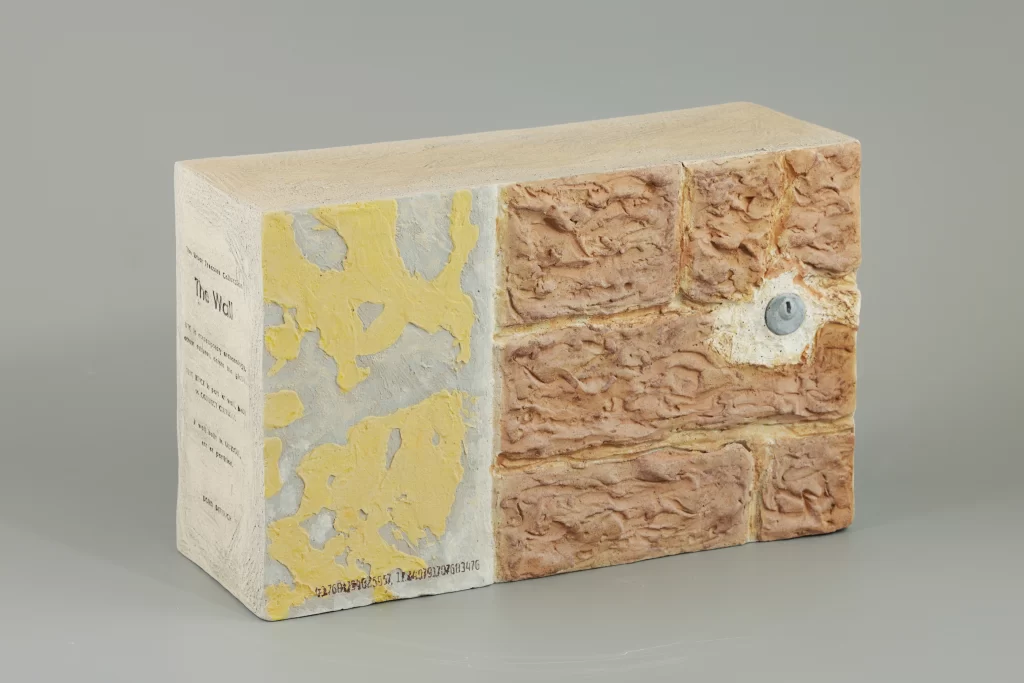

THE URBAN TREASURE COLLECTION

(since 2015, ongoing)

This series is an artistic archaeological investigation of contemporary Western urban space and life.

The core interests of my research are the formal materialisations of a culture’s political, spiritual/religious and artistic mentality and history in the structures and aesthetics of its cities and everyday culture. On-site, I collect motifs and objects to capture the essence of a place, focussing on contemporary aspects.

By reconstructing, referencing or directly using these discoveries, impressions and research, I am creating an archaeo-poetic archive of today’s urban treasures.

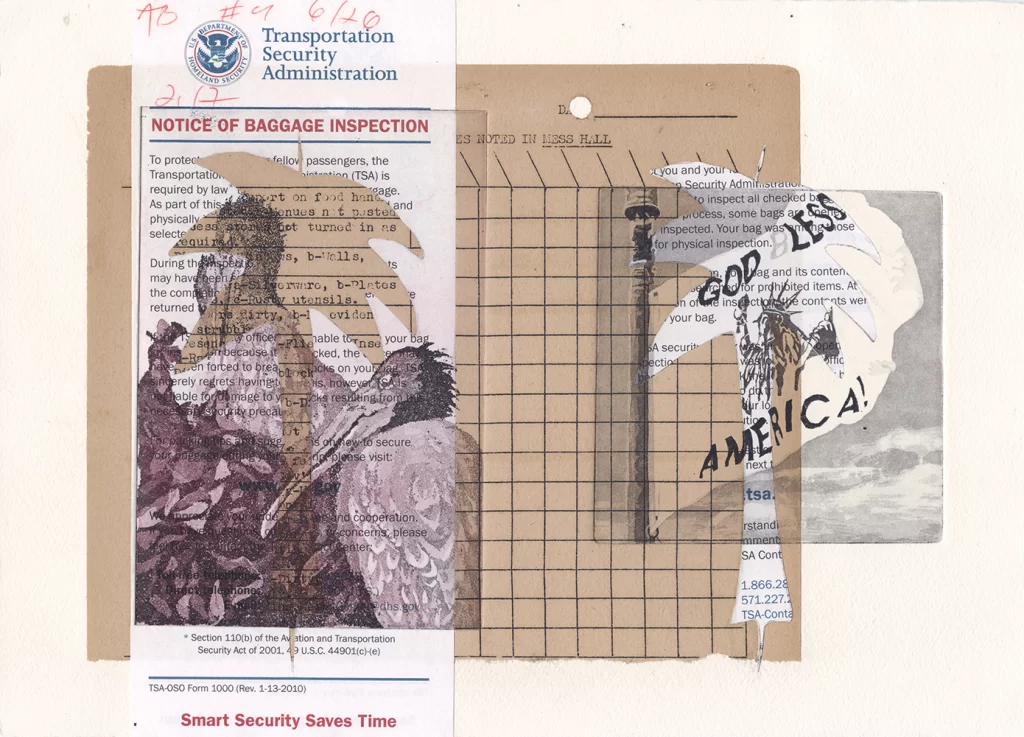

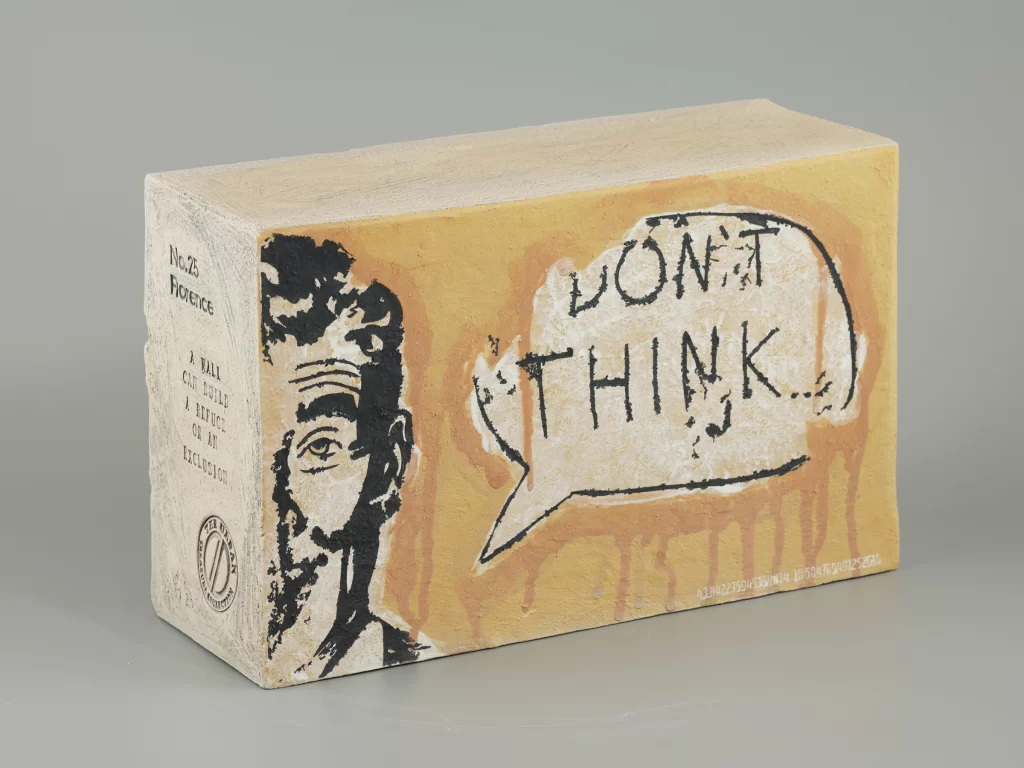

THE WALL (against walls)

(since 2016, ongoing)

A wall can create a refuge or an exclusion.

Deeply influenced by the Europe of the Iron Curtain – and its fall – in my childhood, this ongoing series is my plea for connection, not separation.

The bricks, whose motifs I collect on attentive journeys through various Western cities, create a permanent ceramic monument to the Ephemeral and the beauty in the banal. They build a wall that unites cultures.

GODS OF OUR TIME

(2014)

“What are the gods of our time?” The motifs are based on online keyword research (technology, consumption, love) in globally distributed common and rare languages. I declared the icons, appearing in all languages, as “universal” for our time. Formally, I was inspired by depictions of gods from various lost cultures and art-historical primal forms such as the egg, which for me can even be found in the veil of the Virgin Mary.

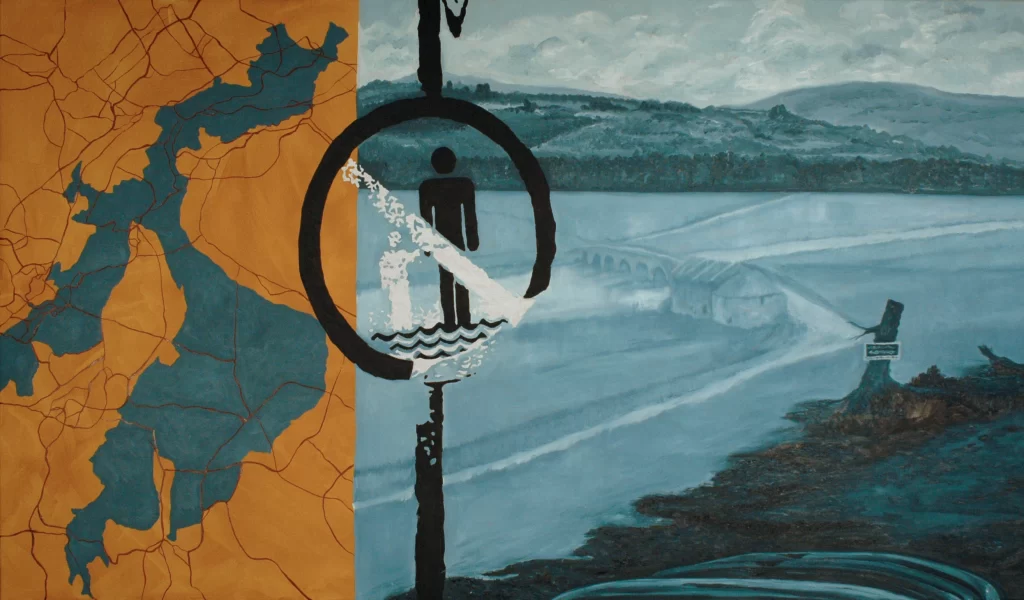

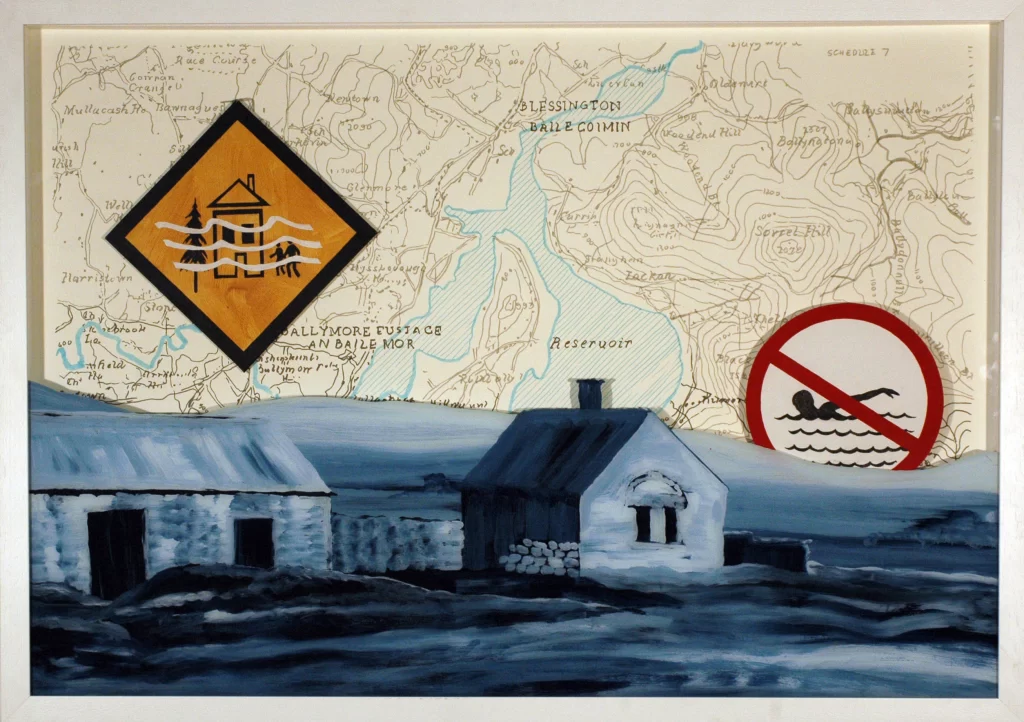

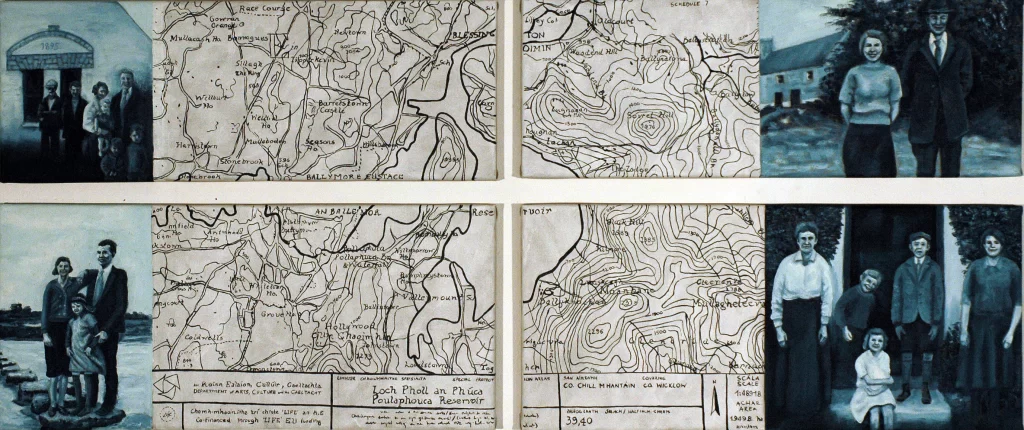

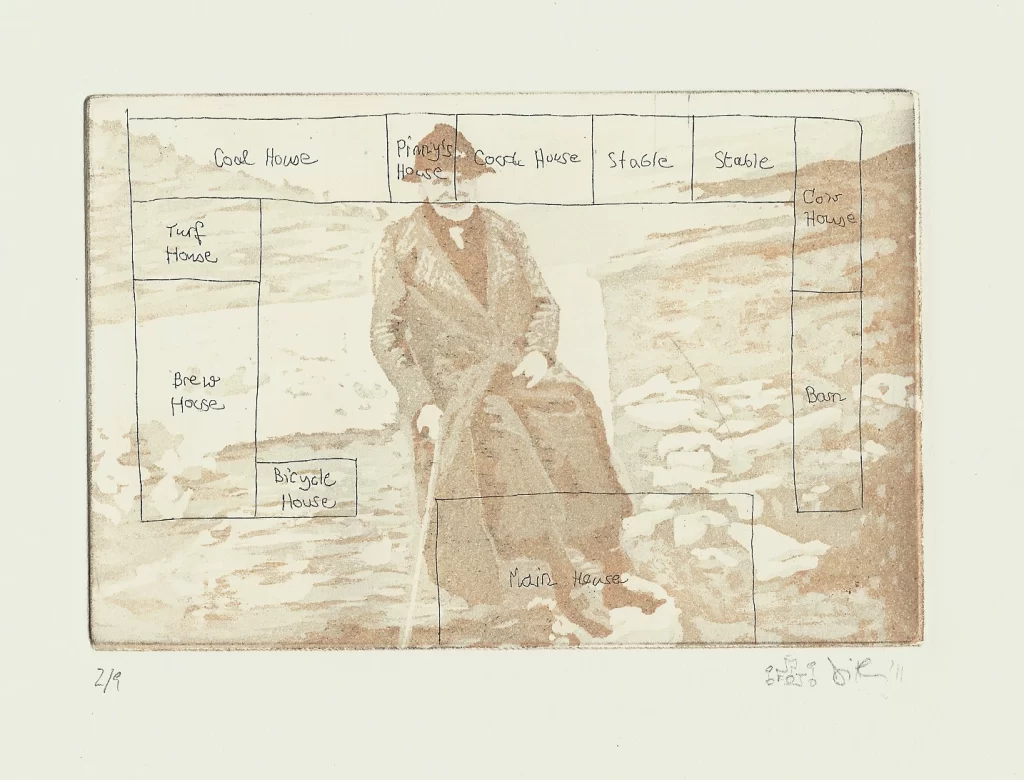

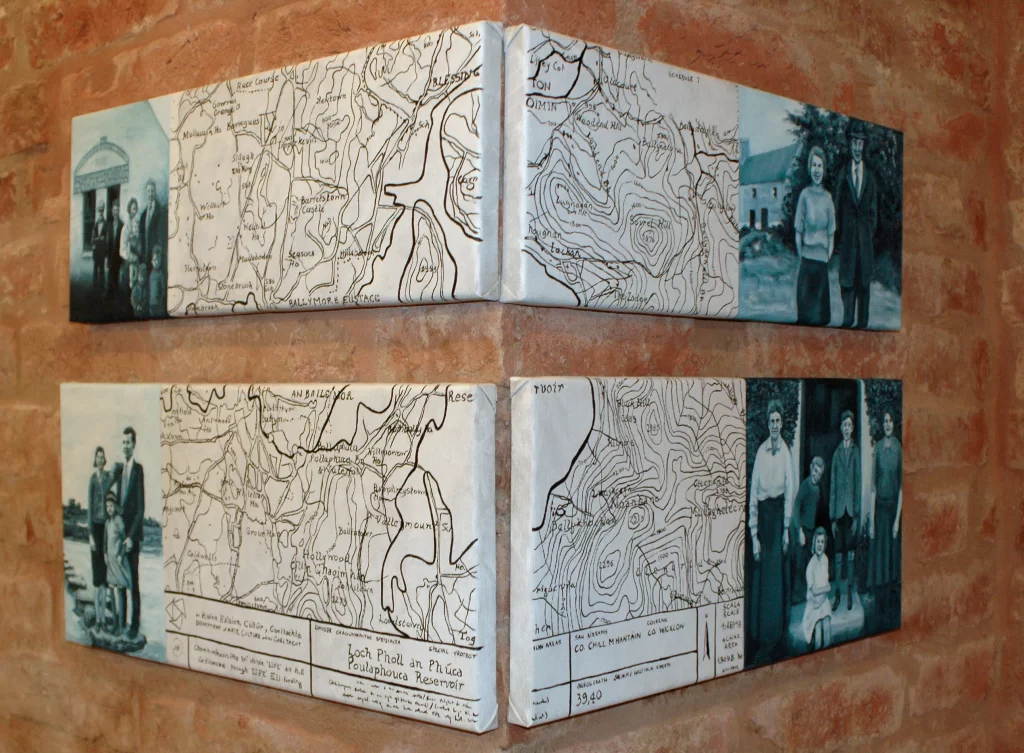

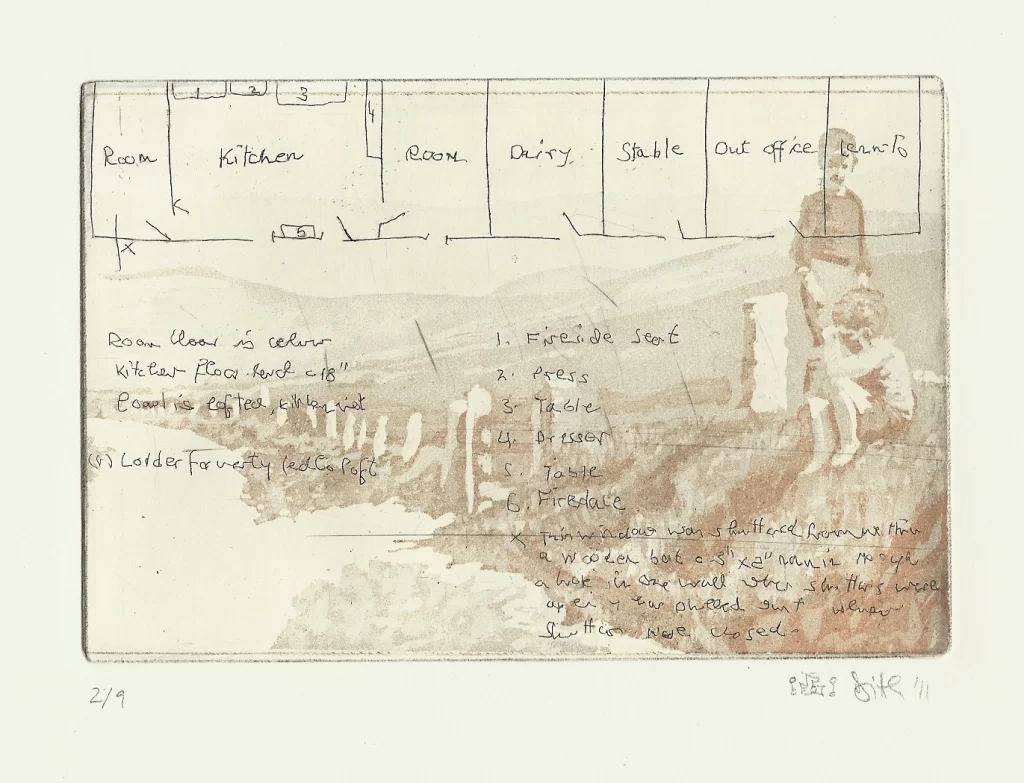

POULAPHUCA STORY

(2011)

The Poulaphouca Reservoir is an Irish dam in Co. Wicklow, built around 1940 to supply Dublin with electricity and fresh water.

In the last summer before the flooding, a team of amateur archaeologists captured what they could of local folklore and stories about the soon-to-be flooded houses and their inhabitants. This multidisciplinary series was created from impressions collected on-site and the archaeologists’ archive as visual material of what had been lost.

Exemplary of all other dams, it is dedicated to what is lost and gained due to progress.

MONUMENT TO THE MOMENT: SPERO

(2013-2016)

.spero.

Collectively, we embark on a pilgrimage to Macchu Picchu, to the pyramids, and even reconstruct the Lauscaux cave so that we can all manage to see it. We visit Stonehenge at the solstice and are fascinated by the Moais of Easter Island. We are tracing these prehistoric people and their cultures…

… because we have a yearning …

A vague, collective longing – certainly not for the external circumstances, we know about the harshness of the living conditions of an Ice Age man carving a filigree sculpture from a bone.

Is it a craving for the fulfillment of a basic human need that we see manifested in ancient cultures, but which seems hard to find in our time?

The need to create, to erect a monument to oneself or an idea – and the longing for a society that offers the necessary conditions?

Is it about the wisdom those peoples appear to have had, their connection to nature and magic, which we sense in their works of art?

Is it just a question of interpretation and prehistoric humans did not perceive their monuments as such? After all, we too are building artificial islands in the shape of palm trees, and high-rise monoliths, submerging concrete monuments to drowned people in the Mediterranean and placing ceramic inscriptions on its shores…

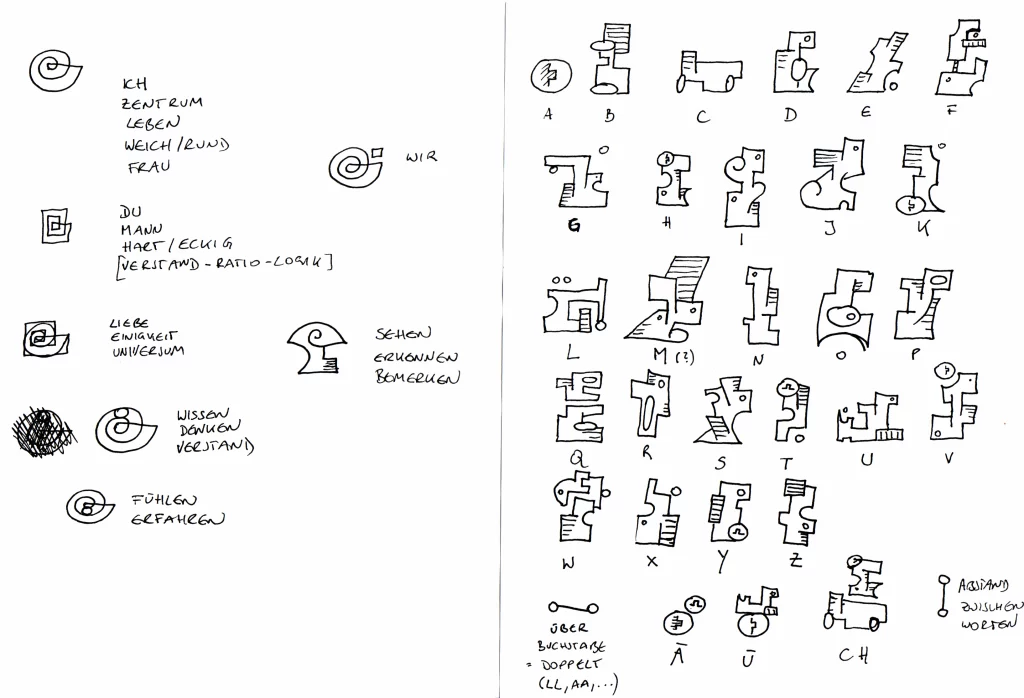

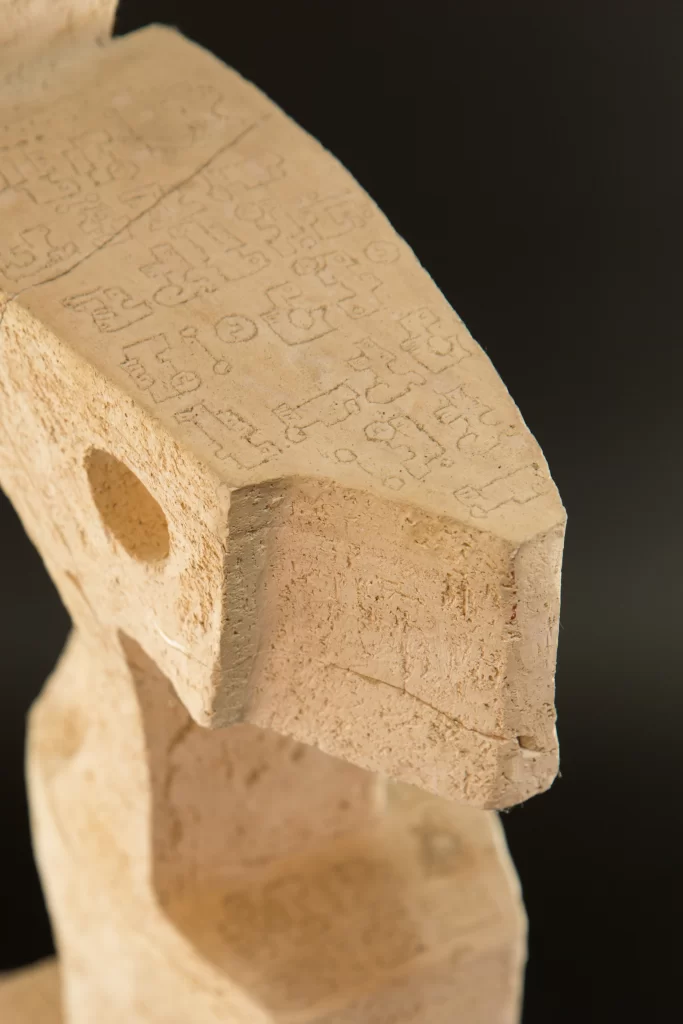

ARTEFICTION

(2005-2013)

Archaeology has fascinated me since childhood. In the course of my studies of Celtology I began to wonder what archaeologists of the future will find in our time layer. For my diploma thesis in Sculpture in 2006 I developed a fictitious culture to offer archaeologists of the future an alternative to the masses of garbage. In comparative, rather artistic than scientific preliminary studies of different cultures to create my own, I was concerned with the following questions:

- What constitutes a culture, and what are its symbols?

- How does it handle its resources?

- What is the significance of art? Is it free or does it serve a purpose, and if so, which one? What forms does it take?

- Is there coherence in the formal language of writing, sculpture and architecture?

- What is the relationship between mythology and art?

- What values will be reflected in the remnants of Western culture?

My approach was subtly critical, questioning and playful.